Unless you live a life of extraordinary privilege in a bubble somewhere, 2016 has rendered politics something that cannot be ignored, brushed off or waited-out for four more years. Post-Brexit, post-Trump and post-any semblance of normality, the assumed rights of many – ones that have often taken years of struggle to obtain – have been plunged into uncertainty by the events of the past months. And, while we cannot be certain of the exact consequences of these events, it’s fair to say that the coming years should not be met with political apathy.

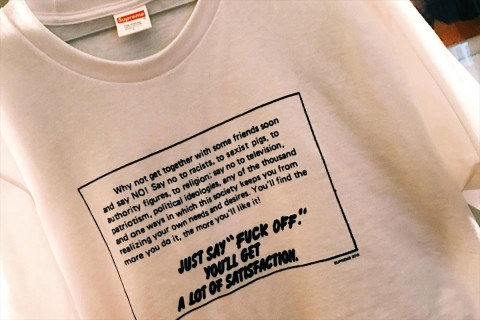

Supreme recently released a T-shirt which read: “Why not get together with some friends soon and say No! Say no to racists, to sexist pigs, to authority figures, to religion; say no to television, patriotism, political ideologies, any of the thousand and one ways in which this society keeps you from realizing your own needs and desires. You’ll find the more you do it, the more you’ll like it! Just say “fuck off.” You’ll get a lot of satisfaction.”

Naturally, this small, defiant gesture sold out, as does much of Supreme’s product. However, its release was notable not only because it echoed the sentiments of many of us, but because it ostensibly addressed the perceived sense of political apathy amongst its consumers.

Supreme consumers are predominantly young, male and, if the lines outside their stores are a helpful metric to go by, largely white. Supreme’s message was defiant, angry and outspoken, but it was also somewhat unexpected. The T-shirt felt more like a forgotten relic of streetwear’s formative years, before it even came to be called “streetwear,” when brands readily used their products to make political and social statements. As a subculture spawned by societal outliers, subversive messages printed on blank tees made up much of the lingua franca of the scene’s early pioneers.

Supreme

In the mid-to-late ’80s and early ’90s, streetwear’s pervasive consciousness was a hallmark of the genre’s output: Fuct’s flip on the classic Ford logo seemingly challenged the concept of capitalist America; Don Busweiller’s Pervert was questioning societal norms (he even named his Miami-based store “Animal Farm”) and black-owned labels like PNB were calling out racial injustice and celebrating their blackness.

Before streetwear became big business, politics were never something to shy away from. “It is something that I think most people either don’t know or have forgotten, which is that being socially-conscious is at the very root of streetwear,” says Chris Gibbs, owner of Union Los Angeles and a seminal figure in they early years of New York’s emerging streetwear scene. “When it first came in to being, it came about as an option outside of the bigger, corporate brands that were around.”

“Before streetwear, you’d often wear something from your favorite team or band or sports brand,” he continues, “Or, taking it a step further, a lot of kids would wear clothing from brands that didn’t represent them at all, and some of these brands didn’t even want young – particularly black – people wearing their clothing to begin with. So, young designers started making clothing for themselves and their communities.”

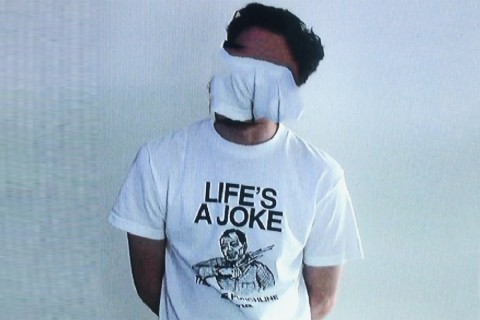

Burma

Last year, under Gibbs’ guidance, Union LA launched a series of collaborative T-shirts highlighting racial injustice in the U.S. It was a theme picked up on again a few months ago by nascent New York label Noah, which is owned by Gibbs’ friend and ex-Supreme creative director Brendon Babenzien. The T-shirt championed the work of the Black Lives Matter movement, with all proceeds going directly to the organization.

“In this case specifically, I was mostly speaking to white folks, who are generally either completely ignorant or would rather not admit there is a problem,” writes Babenzien over email. “Both of those are unacceptable to me. We are not a society if we allow half of our society to be abused. Most white people don’t have the opportunity to get perspective on this issue, because they never actually experience what black folks experience. We can never understand.”

“We definitely wanted to raise awareness and money,” he continues. “We’re pretty small, so we’re not changing the game with the money we raised. But the debate might have some small impact. Our approach to everything is brick by brick.”

LA-based label 424 has drawn on similar themes with recent releases, including a T-shirt with a picture of riot cops emblazoned on the front and the slogan “we’re here to help.” The label has also released a collection entitled “Oil Money,” with all the geopolitical innuendo that entails.

Meanwhile in London, fledgling label Hypepeace have been riffing on the Tri-Ferg logo of Palace in order to raise funds for Palestine’s Sharek Youth forum, which provides “a platform for Palestinian youth to meet, develop ideas, think creatively and implement community projects.” It is a creative way of aiding those growing up in the harshest of conditions.

Hypepeace

“There’s a new generation of politically-engaged people, who are unapologetically expressing their solidarity with the oppressed,” one of the brand’s founders told Dazed earlier this month. “[They’re] blatantly expressing this through what they wear, without compromising when it comes to style. It’s rejecting the cliché that we’re this superficial, egocentric, “selfie” generation that only follows the stream and upholds the status quo.”

While these are all small gestures – not one of them will irrevocably change the political or social landscape – that does not diminish their importance. In their own way, each one advances discourse, or perhaps introduces a consumer to an issue they had never paid much mind to prior.

In the context of fashion, few inspire more fervent devotion that the labels at the vanguard of streetwear in 2016 – such a fanaticism does not exist in the luxury market or on the high street. All of which made Supreme’s T-shirt denouncing racism and sexism last week more potent, not just for its message, but because it understood that its voice carried a certain weight and chose to use it.

The power of streetwear has always been its ability to offer an alternative – it is a genre where authenticity is of equal importance as good design; where the ability to agitate and challenge societal norms has generally been accepted as a good thing.

As the next few years loom, shaped by the past year of divisive racial scaremongering, brands cannot ignore the role they play in wider culture. With a larger and more attentive audience than ever, shying away from the bigger issues is no longer an option.

Speaking of politics, why don’t we care about celebrities with mental health issues?

-

Lead image:

Samira Bouaou / Epoch Times