An immoveable pillar of international street fashion, Hiroshi Fujiwara has seemingly been a permanent fixture on the scene since time immemorial. Given his dabbling via his fragment design imprint in everything from Nike, Converse and Beats by Dre, to Stussy, NEIGHBORHOOD and Carhartt, the man’s influence permeates every aspect of streetwear and regularly tests its boundaries with experimental initiatives such as the POOL aoyama, retaW and THE PARK・ING GINZA. However, rewind some two-and-a-half decades and we return to simpler times, when the entire Japanese streetwear scene was comprised only of Fujiwara and his fledgling graphic T-shirt label, GOODENOUGH.

Preceding the entire Ura-Harajuku movement, GOODENOUGH (often abbreviated to GDEH) was conceived in 1990 when graphic designer and later founder of C.E, SK8THING, floated the idea of creating premium graphic tees to Fujiwara. Having gained recognition as one of the first freelance DJs in Japan, Fujiwara had already become the point man for Western imports into a cultural scene that was ravenous for new sources of inspiration. Speaking to Interview Magazine, Fujiwara explained, “In those days, people were really hungry for information—and, somehow, I had pretty good access because I had friends in London, New York, Los Angeles, everywhere. I’d been visiting many places and talking with people, so I had a constant flow of new info. I sometimes did articles for magazines and things, and people started to say, ‘If you want to know what’s going on, ask Hiroshi.’”

For his new label, Fujiwara took inspiration from the likes of Stussy and England’s Anarchic Adjustment and, in showcasing a skill that he would later become renowned for, went on to deftly mix and match the surf and BMX influences of these brands along with his own hip-hop background to create a palatable aesthetic packaged for budding Japanese tastes in streetwear. GDEH’s early designs thus featured pop culture-inspired graphics that drew on everything from Nascar emblems and psychedelic illustrations of Karl Marx, to repurposing the distinctive logos of Lonely Planet and cult ’80s-era surfwear brand Life’s A Beach. The brand also preceded the bomber and varsity jacket trends by several years, with the rare GDEH collector’s items popping up every now and then on Japan’s Yahoo Auctions.

After the Americana-centric Shibukaji subculture of neighboring Shibuya district, Tokyo’s youth were eager for a new cultural wave and almost immediately latched onto the homegrown, filtered aesthetic espoused by GDEH. Rapidly attracting a cult following, the brand was not so much concerned with youthful rebellion against the strict, patriarchal Japanese hierarchy, but was instead adopted as a form of self-expression. However, it was not known for many years after its founding who was behind the brand — a masterful stroke by its creator. As Fujiwara later explained, “If I attached my name to the brand, only people who liked me would buy it. They wouldn’t be able to see the clothes for what they were.”

In addition to the secrecy surrounding its provenance, GDEH’s pieces were anything but affordable – consciously priced equal to expensive Western designer goods of the time, Fujiwara thus elevated easily-produced and domestically branded garments such as T-shirts, sweatshirts and jackets to heights previously reserved for high fashion. The label’s designs were also released in very limited drops and most often sold out on the same day, increasing their perceived currency in the eyes of its fans. With GDEH, Fujiwara laid the foundation for the most basic tenets of scarcity and demand that form the crux of today’s global streetwear market. These lessons left indelible impressions on the young Jun Takahashi and Tomoaki Nagao, both of whom Fujiwara had taken under his wing in the course of running GDEH. Indeed, Nagao, who was studying fashion and DJ’ed at the time, would be christened “NIGO” by Fujiwara, alluding to his role in assisting Fujiwara with styling as well as on the nightclub circuit.

After learning the ropes at GDEH, Takahashi (who Fujiwara affectionately calls “Jonio”) and NIGO would found their respective brands, UNDERCOVER and A Bathing Ape, and with Fujiwara’s help, the duo opened the seminal streetwear boutique NOWHERE in Harajuku in 1993. In addition to NIGO and Takahashi’s own brands, NOWHERE also stocked Nike and adidas sneakers alongside vintage and deadstock items sourced from America. As press coverage of the boutique mounted within the nascent Japanese hip-hop and streetwear scene, NOWHERE unwittingly became the nucleus around which the Ura-Harajuku movement grew, with Shinsuke Takizawa’s NEIGHBORHOOD and Hikaru Iwanaga’s Bounty Hunter later adding their own flavors to the area.

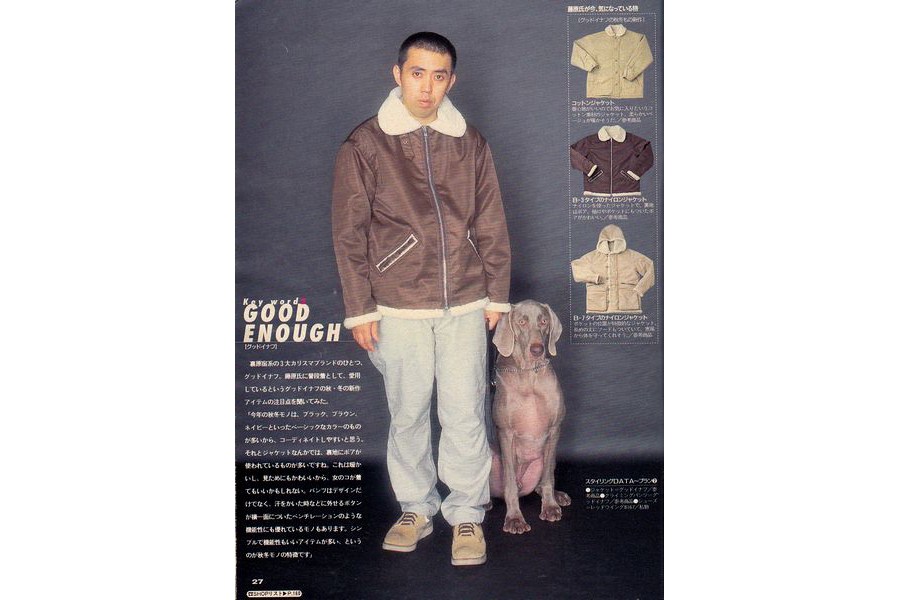

Hiroshi Fujiwara wearing a GOODENOUGH mouton jacket in the October 1999 issue of Street Jack magazine.

From there on out, GDEH continued to operate under Fujiwara’s oversight, briefly opening a boutique in London under the GOODENOUGH U.K. label, a diffusion label called RESONATE GOODENOUGH in 2004, a West Coast preppy-influenced label called GOODENOUGH IVY in 2013, and more recently, a Stateside capsule collection with UNDEFEATED earlier this summer. However, Fujiwara himself gradually lost interest in the brand that had started it all towards the end of the ’90s. “I decided that this is not what I should be doing. I didn’t want to make a big company and have to hire lots of people,” he explained. “I felt like I was better as an independent or as a solo operator. So I made the decision to finish everything and work alone just with an assistant or two and just change to a design studio that sells ideas to other companies for a percentage or a guarantee. Although maybe there isn’t the potential that there is in having a bigger company, it’s good for me.”

Having firmly established his reputation as the “Godfather of Streetwear,” Fujiwara would go on to helm influential projects such as Nike’s hallowed HTM collaboration with Mark Parker and Tinker Hatfield, as well as collaborating with Levi’s on its Fenom line, among others. And despite losing the creative capabilities of its founder, the brand holds an inalienable spot as a pioneer within Japanese streetwear for its success in injecting style and flow into a fashion industry that had anything but. Commenting on the brand’s phenomenon, former Stüssy creative director Paul Mittleman succinctly says, “I think the simple ideology of GOODENOUGH was appropriate – the majority of what was around was simply not ‘good enough.’” Regardless of its future fortunes within the fickle streetwear industry, GDEH wasn’t merely good enough — it was the precursor to a worldwide style revolution.